There are more than a thousand natural springs in Florida. They are prehistoric, beautiful, world-famous, and draw thousands of visitors and millions of dollars to the state every year.

On weekends, springs are crowded with people swimming, boating, enjoying picnics, or snoozing near waters, which hover at 72 degrees year round.

The unsurpassed beauty has been featured in art, photography, music and even films. For many the springs hold a deep mystery that they believe is healing, spiritually and physically.

In addition, these ecological gems provide a window into Florida’s supply of potable water. We injure them at our peril, according to researchers and concerned citizens.

If the springs are healthy, and if there is ample abundant clean water, that will positively affect the health of the community and the local economy,” said environmental scientist Carol Lippincott.

The paradox: we may be loving these incredible resources to death.

An Imperiled Resource

By some estimates more than 60 percent of Florida’s springs are impaired in some way.

Impairment may be anything from high nutrient concentrations to low flow levels. The causes vary and include overconsumption of groundwater by Florida’s 19 million residents from private and municipal wells, by high rates of pumping in the agricultural sector and through manufacturing use.

Spring health also deteriorates from runoff from fertilizer use. Human activity in and near the springs causes battered shorelines, trampled native aquatic grasses and stressed wildlife.

Bob Knight, director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute speaks at Rally for the River, Palatka, Fla.

Sea level rise threatens salt water intrusion—even more dramatically when coupled with overconsumption, which can draw portions of the aquifer below sea level. A decades-long drought has significantly decreased rainwater that percolates to the aquifer and recharges it, which is the source of the springs that Floridians and visitors alike enjoy.

Signs of disaster are all around the state, said Bob Knight, an advocate for the springs and director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute.

The first sign of a deteriorated spring is reduced biodiversity. “The most senstive native species of aquatic grasses disappear. This is currently happening in many springs,” he said.

Knight, who also teaches at the University of Florida, said he is concerned that the capacity to provide water for people and the springs has been exceeded.

“Ichetucknee is showing signs of eutrophication and declining flows. You can walk across parts of the Santa Fe and Suwannee rivers. White Springs is nothing more than a sinkhole,” he said.

Burt Eno, president of Rainbow River Conservation Inc., is especially critical of the agricultural sector’s central pivot irrigation systems, which result in significant amounts of evaporation. “Water never gets a chance a chance to trickle back down into the aquifer,” he said.

The springs are a window into a deeper concern for Floridians. The health of the springs is a measure of the health of Florida’s freshwater supply. Experts and citizens are becoming alarmed about the future.

“It’s not a pending water crisis. We are in a water crisis,” said Carol Lippincott, who has worked in natural resource protection for 24 years. As a former senior environmental scientist with the St. Johns River Water Management District, Lippincott learned firsthand about the threats to Florida’s water supply.

“Water management districts across the state have notified local governments that there is no more ground water for them to withdraw. Local governments must start conserving water in much more meaningful ways,” she said.

Lippincott has also worked with communities to protect springs, which she said have a tremendous social, ecologic and economic impact.

Chapter 1

Geology of Water

Although surrounded by water on three sides, Florida’s true hydrologic treasure is the network of 7,800 lakes that dot the state and the 1,700 spring-fed rivers that spider the landscape on their ways to the sea.

Although surrounded by water on three sides, Florida’s true hydrologic treasure is the network of 7,800 lakes that dot the state and the 1,700 spring-fed rivers that spider the landscape on their ways to the sea.

These once abundant and pristine waters have laced the peninsula for eons, sustaining water supply and supporting ecosystems to the benefit of wildlife and indigenous people.

The rivers are fed by springs that are entwined and interconnected in porous limestone labyrinths deep beneath the ground.

Two categories of springs are found in Florida. Seeps are shallow, slow and generally at the level of the water-table.

Karst springs, though, are what make Florida so famous. These artesian springs discharge—often with tremendous force, through openings to the surface from cracks, crevices, and caverns under pressure deep underground.

The most abundant concentrations of springs in the world are located in northern and central Florida. Wakulla Springs, just outside Tallahassee, claims the distinction of being the largest and deepest spring on the planet.

Florida’s springs originate from geologic activity dating back to the Eocene and Miocene ages—as long as 55 million years ago, according to Jeff Davis, hydrologist with the St. Johns River Water Management District. Millions of shells and skeletons from sea life have since accumulated and hardened into calcified rock formations.

A limestone core shows the porous quality of the Floridan aquifer.

Sea level rose and fell covering and uncovering the peninsula over millennia. As the Appalachian Mountains eroded, Davis said, sand and clay were deposited to Florida, allowing the formation of “confining units,” that accumulate water. Ponds and lakes that could hold water formed. Rainwater, which is slightly acidic, filled those spaces and slowly dissolved the limestone substrate, creating tiny holes, crevices and, in some cases, sinkholes and large underground caves.

The Floridan aquifer is 100,000 square miles of this underground limestone matrix that holds, experts say, nearly 2 quadrillion gallons of potable water suspended above a level of saltwater.

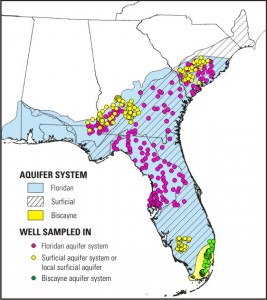

This bounty, subject to the vagaries of whatever happens on the surface, is shared by other states in the Southeast. The Floridan Aquifer stretches beneath the ground to South Carolina and includes portions of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi.

Florida’s springs are a direct result of this ancient geological formation. The interconnected crevices, cracks, caves and tunnels are the “pipes” through which water flows to the springs.

When new water enters the system through rainfall and percolation, pressure is exerted on the water already there, which forces it to the surface. The magnitude of this upward force is the result of the number of caves leading to the spring vent, and the diameter of the vent.

Spring flow is directly related to the health of a spring’s ecosystems as well as a good indicator of the amount of water in the aquifer.

The Aquifer and Spring Flow

The more water that Floridians, and our neighbors, pump out of the aquifer, the lower the level in the storage tank gets, and the slower springs flow. This creates an imbalance in ecosystems and can cause springs to stop flowing entirely.

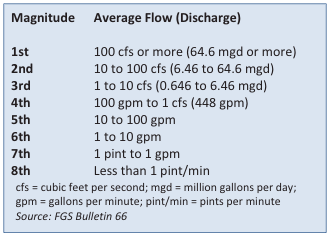

Springs are measured by a system called “magnitude.” Florida has 33 “first magnitude” springs that exceed flow rates of 100 cubic feet per second. That’s about 64.6 million gallons per day.

No less impressive are the next 340 “second” and “third” magnitude springs that drive water to the surface at rates between 600,000 and 64 million gallons per day.

Matt Cohen, a systems ecologist and hydrologist at the University of Florida, is not fond of the absolute statement “all springs are drying up,” which he noted “seems to be a meme floating around.” And while some springs are drying up, others are managing to sustain historic flow rates, he said.

“It has been a pretty dry decade,” Cohen said. The lack of inputs—the rain—must be factored into the mix of whether overconsumption or drought is playing a larger role in the reduction of springs flow, he said.

What Cohen called the “poster child” of dried up springs, Kissengen in southwest Florida, ceased flowing in the 1950s. Located at the north end of the Peace River, its demise has been blamed on hundreds of wells drilled into the aquifer in the springshed.

The aquifer is like a big Slurpee cup,” said Bob Knight, director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute and president of a wetlands consulting business.

“Just imagine,” he told a group of students doing research in Kings Bay in Crystal River, Fla., “that there are lots of straws and everyone is pulling out water at the same time.”

But there are no refills—except rainwater.

Getting that rainwater into the aquifer is not easy or quick. Some of the rainwater evaporates immediately, Knight said.

The surface landscape determines how much water ends up back in the aquifer, the reservoir that feeds the springs. If the surface is natural (with plentiful vegetation), about 10 percent will run off (eventually into the sea), 40 percent will evaporate or be taken up by vegetation, and as much as 50 percent will seep into the aquifer.

However, if a landscape is covered with roads, parking lots and buildings, up to 55 percent may run off, 30 percent will evaporate and as little as 15 percent or less might make it into the aquifer.

The rainwater in some places must seep through thousands of feet of sand, clay and limestone crevices before reaching those prehistoric caverns that have stored Florida’s water for millions of years. Recharge rates vary from less than one inch to more than 20 inches per year, depending on local geologic and hydrologic conditions. Typically in the central Florida peninsula recharge is slow, according to the U.S. Geologic Survey.

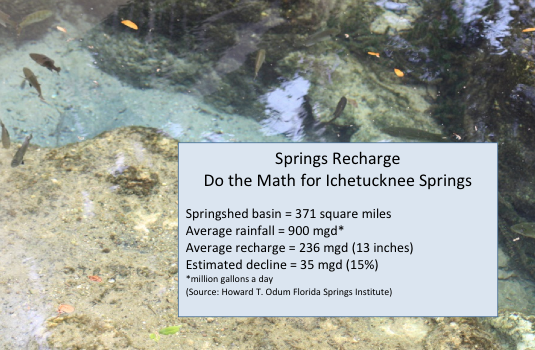

Recharge, in some cases, is not keeping up with consumption. For example, the long-term flow decline in Ichetucknee Springs, located in Suwanee and Columbia counties, is about 15 percent.

Spring flow is what fills up spring runs which seamlessly turn into rivers and creeks. Many rivers in north and central Florida are spring runs, Knight said.

Reduced flow may impair springs in other ways such as reducing dissolved oxygen and promoting algae growth.

Chapter 2

Over consumption and Drought

Signs of problems in Florida’s springs are all around us. Parts of the Santa Fe River, for example, are so dry that canoeists must portage their canoes dozens of times to make a single run.

Worthington Springs and White Springs have completely dried up—“they are nothing but sinkholes now,” Knight said. This scenario plays out all over Florida. The groundwater source for any spring in the state, is the same water source for human consumption, be it a private well or a public utility.

“The same depleted aquifer that feeds the Santa Fe and Suwannee rivers and their springs, is the aquifer that waters yards in Gainesville, Newberry, Archer, Hawthorne, Lake City, Live Oak and hundreds of other small and large human enclaves,” said Bob Knight, an advocate for the springs and director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute.

About 260 artesian springs along the Suwannee River, for example, naturally pump an estimated 2.8 billion gallons a day from the aquifer. Withdrawals for human consumption and industry amount to 245 million gallons a day.

“Although that is a small fraction of the flow,” Knight said, it starts to add up. “Especially when you realize that Jacksonville and coastal Georgia are pumping water from the same aquifer.”

Groundwater pumping in northeast Florida is pushing the groundwater divide to the west, encroaching more and more on the rainfall recharge area that historically fed the springs and rivers. Data published by the U.S. Geological Survey indicates that pumping in the Jacksonville area is pulling down the levels of the aquifer—about 35 to 40 feet in the last 60 years.

“A very small decline in groundwater levels will slow the springs flow,” he said. Unfortunately, at this point, much of the water that Jacksonville withdraws discharged into the St. Johns River where it flows out to sea instead of percolating back into the aquifer.

When water is used wisely, according to Florida’s water management districts, and returned to the ground, it percolates slowly back into the aquifer for reuse by humans. Resupply from percolation and rain means spring flow can be sustained. Rainfall and storage, however, are becoming challenges in Florida.

Climatologists have pointed to the conversion of wetlands to development and agriculture as one of reasons for less rainfall in the state. Water that evaporates from wetlands, rivers, and lakes is the catalyst for locally generated rainfall.

In a 2004 study, Curtis Marshall and Roger Pielke of Colorado State University, determined that land use changes in Florida over the past 100 years have significantly decreased summer rainfall and increased temperatures in Florida. When wetlands in Florida are converted to agricultural and urban use, we lose the natural surface storage areas for the water, the study reported.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, “more than half of Florida’s 36 million acre peninsula was submerged,” journalist and author Cynthia Barnett wrote in her book Mirage.

Since that time, development and agriculture has reduced that wetland area to less than 9 million acres, according to recent figures from Florida Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration.

Restoring those missing wetlands may be one of the keys to increasing rainfall in Florida and replenishing water supplies that feed the springs.

Chapter 3

Green Slime

No one wants to go swimming in green slime. But jump into a cool Florida spring and that’s what you may find. Springs in Florida are being overrun by a noxious aquatic weed that grows in thick gelatinous masses, hanging in the water or forming mats on the bottom of spring runs.

Besides a deterrent to enjoyment, Lyngbya wollei are an ecological disaster for native aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. The presence of this algae is often a signal of high nitrate levels in the aquifer supply, which can be toxic to people and animals, said Stacie Greco, water conservation coordinator with Alachua County Environmental Protections Department.

Public water is tested routinely for nitrate levels and other chemicals, but those who depend on private wells for drinking water should have water tested regularly.

One of two billboards on I-75 in Florida sponsored by the Florida Water Coalition to “educate Floridians and visitors about the state’s widespread algae pollution problem.”

The unchecked growth of this native algae began in the mid 1980s, according to researchers and residents who use the springs, and until recently has been tightly correlated with increased nitrates in Florida waters.

Lyngbya are a type of cyanobacteria and can be toxic to livestock and pets. The algae have caused human health issues, including respiratory problems, rashes, and stomach ailments, according to a 2004 report prepared for the Florida Department of Health by an environmental engineering firm in Jacksonville. Details about toxic algae in Florida are available on the Florida Department of Environmental Protection website.

Citizens, environmental activists, researchers, various state agencies, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are engaged in trying to slow down and remove the algae growth and set standards for measuring it.

While political and legal forces wrestle with the standards, scientists seek causes. For decades algae overgrowth has been attributed to high levels of nutrients in the water, such as nitrates found in fertilizers, manure and sewage.

New theories point to causes besides nitrate levels. Lack of dissolved oxygen is one; another is the decreased flow rates, or discharge of Florida springs from the aquifer. The answer may be all of the above, according to researchers.

The first scientist to look into springs and river aquatic ecosystems in detail was Howard T. Odum. From his extensive studies of the Silver River, near Ocala, Fla., in the 1950s Odum developed a complex matrix of interactions that is still taught as a standard for ecosystem research.

One glance at Odum’s visual description of an aquatic ecosystem is enough to see that the number of possible relationships for cause and effect outpace an easy answer to what might be causing the algae overgrowth.

Two of his former students, Bob Knight, director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute and Matt Cohen, a systems ecologist and hydrologist at the University of Florida are engaged with their own students in solving the problem of the algae proliferation in Florida’s springs. Their approaches though, are different.

“It is very reasonable to say that nitrates are the cause of what ails the springs. I wouldn’t reject that hypothesis, but it is dangerous not to entertain other mechanisms,” Cohen said. If algae, for example, is kept in check by grazers, which Knight also sees as a possibility but perhaps for different reasons, then grazers might be affected by levels of oxygen in the springs.

Matt Cohen, hydrologist and systems ecologists at the University of Florida taking flow readings at a creek.

Cohen and his fellow researchers do not see nitrate levels “correlated with algal abundance across a broad population of springs that have been sampled. They theorize and are now testing a relationship between dissolved oxygen, grazer density, and algal blooms.

Knight has proposed an alternative hypothesis that points to elevated nitrate concentrations as a cause of observed loss of native vegetation, and subsequently an increase in filamentous algae.

“The elevated nitrate concentrations in combination with other stressors—such as low oxygen, reduced flow rates, trampling, aquatic herbicides—are stressing or eliminating the dominant native aquatic plants in the springs,” he said. This allows the Lyngbya to take over, he proposes.

Knight believes that “this is allowing increased dominance by the filamentous algae species that have otherwise always been present at low densities.”

Vexing for these researchers is a current lack of consistent patterns. Some springs have filamentous algae but normal rates of nitrates and dissolved oxygen. Some have high nitrates and no filamentous algae.

Silver Glen Springs in the Ocala National Forest, for example, has almost no nitrates, but an explosion of filamentous algae. What’s different? For Knight, it is that “native aquatic grasses are disappearing in the spring runs.”

A 1,500 percent increase in algae in the springs at Weeki Wachee State Park, south of Crystal River, required intense restoration by the Southwest Florida Water Management District. In 2001 the former tourist attraction and home of the Weeki Wachee World Famous Mermaids, was acquired by the state. In addition to heavy deposits of sand, silt and muck, the filamentous algae had invaded the spring.

As students of Odum, Cohen and Knight strive for a “whole systems” approach to their work. Eventually they may find that they are putting together pieces of the same puzzle.

Chapter 4

How We Affect the Springs

You may not live near a spring in Florida, but your daily activities likely affect at least one. When you fertilize your garden and grass, water your lawn and wash your car, or linger in a hot shower, you affect the springs that flow from Florida’s deep underground aquifer.

Use too much water and you contribute to low flow rates. Fertilize too much and you add nutrients that cause eutrophication—an overgrowth of vegetation. Both result in degradation of Florida springs and decrease drinking water resources.

Everyone living in springsheds, also known as a recharge areas, can compromise the health of a spring. There are scores of springsheds in Florida that can across hundreds of square miles. River basins are even larger and include springsheds. The unique geology of Florida makes water a shared experience.

Water from your yard percolates through sand and limestone to the Floridan aquifer, which is then recharged into springs that flow into Florida’s rivers. Nutrients from fertilizers, septic tanks, and manure, and pollutants such as manufacturing waste and runoff from highways may flow directly into springs and rivers. Or they may percolate, along with the rainwater, hundreds of feet into the aquifer.

The challenge for Floridians is how to protect this vital resource without stifling growth or unfairly impinging on people’s enjoyment and use of the springs.

“I’m optimistic for several reasons,” said Carol Lippincott, a native Floridian and environmental scientist. “I believe in the capacity of people to make good decisions when they are well guided.”

In addition, she said “Florida’s water law is very protective of water resources, yet still allows ample opportunity for economic vitality in the state.”

One of the missions of six springs basin working groups established in 2001 through the Florida Springs Initiative was to reconcile this dichotomy. The idea was to create an atmosphere of collaboration for economic development and support for healthy ecosystems within springsheds—thus protecting the state’s water supply.

For each working group, stakeholders, citizens, environmental groups and government agencies were brought together for quarterly meetings. These forums facilitated open dialogue, education, and strategic planning for communities, Lippincott said.

“I think it is safe to say that there is a universal attraction to Florida springs,” said Lippincott, who spent four years facilitating two of the springs working groups.

“When people spoke about why they value springs or their experiences with springs, it was unanimously a positive experience,” said Lippincott, who facilitated the groups through her consulting agency, “Floridia.”

In fall 2011, the groups fell victim to state budget cuts. “The state made it clear that the cuts were for lack of funding, not lack of support,” Lippincott said.

Some of the groups have continued on their own initiative. Lippincott, for example, helped Volusia Blue Springs reform under another nonprofit agency and stays in touch with members.

The Silver Springs working group has reverted to its original forum as a citizens’ initiative and has filed for nonprofit status. Called the Silver Spring Alliance, the group is currently engaged in a battle against the development of a 30,000 acre cattle operation that has filed for a consumptive use permit for 13.2 million gallons of water a day from the aquifer.

The Santa Fe Springs working group is currently facilitated by Stacie Greco, water conservation coordinator with Alachua County Environmental Protections Department.

The sphere of concern about the springs, however, needs to radiate out more than just a few miles from the actual spring, said Peter Colverson, who co-facilitated three groups through an environmental services company Normandeau (formerly Pandion).

Protecting the springs requires behavior change, he said. “And that is a very hard sell. How do you create a connection between someone who lives in Williston, their everyday activities, and Rainbow Springs, which is 50 miles away?”

Put very simply, Colverson said, “Why should they care?”

The closer you live to a spring the more likely you are to care about the quality and quantity of the water and protection of the ecosystem. Those are the preliminary findings of University of Florida graduate student, Diana Alenicheva. She mailed 1,800 questionnaires to residents of two springsheds in north central Florida.

Based on analysis of the 518 responses, Alenicheva noted that concern for local springs increases to some degree with residential proximity. Her questions covered topics such as algae blooms, water clarity and plant health.

She also discovered that the organizations most trusted by those living within the springsheds were the springs basis working groups. Nongovernmental environmental groups, scientists, and Florida Department of Environmental Protection were closely matched for second place.

Alenicheva, who has just completed a master’s of science in Interdisciplinary ecology, indicated that study provided rich data that will undergo further analysis.

Burt Eno of Rainbow River Conservation, Inc., said that community effort is the best way to protect springs and rivers in Florida. The Rainbow River group, founded in 1962 and incorporated in 1991, is one of the oldest in the state and has 200 paid members, a quarterly newsletter, and a website.

Rainbow Springs, the source of water for the river, is one of the many former amusement parks in Florida that have been purchased by the state for public use. The Rainbow River group sponsors clean ups, educational programs and works closely with stakeholders and residents.

Eno said they actively participate through local government and when necessary join or support legal actions to protect the springs. Currently the group is fighting a 256-acre, 400-unit development proposed along a mile and a third of the riverfront.

Colverson believes that strategically the emphasis should be on water protection rather than springs protection. Everyone pays attention to potable water resources, he said, but as Alenicheva’s preliminary results show, not everyone is concerned about the springs.

Colverson and Lippincott independently agree that the best way to manage water resources in Florida is to engage local citizens in the decisions.

Colverson said in his experience the state environmental protection agency “shies away from enforcement” and prefers that communities work together to solve water resource problems.

Stakeholders and residents with mutual goals and needs are more likely “to find common ground” and “work together on issues that will be beneficial to springs and at the same time beneficial to the local communities and their economies,” Lippincott said.

Chapter 5

Sacred Springs, Healing Springs

For Mary Rockwood Lane the springs are a sacred experience. “There’s magical energy in the springs. There is an ancient ancestral spirit that lives there,” she said.

As an artist, nurse, and author, Lane has spent much of her energy investigating the healing potential of sacred sites all over the world as well as sharing with others how to tap into personal natural healing forces.

“If you go to all the sacred spots in the world, they are all at intersections of water. Often near a spring. The hub of human and animal life was at the springs,” she said.

Christopher Witcombe, professor of Art History at Sweet Briar College in Virginia has written that “the identification of the sources of rivers, streams, springs and wells as sacred is very ancient. Often it was claimed that the waters healed the injured or cured the sick with the result that well or stream came to be regarded as a sacred shrine.”

Lane, who teaches transformational workshops about art and healing, considers Florida’s springs some of the most powerful spots on the planet.

She found the headsprings of the Ichetucknee River a motivating place for her own healing journey and creative work. “For years I went to springs to inspire me to write every single book I ever wrote. The springs were like a creative force that flowed through,” she said.

Lane often takes people to the springs as part of workshops or ritual. She finds that people respond positively to the experience. “When people go to the springs, they immediately get connected on a deep level. It’s like a baptism. Like a holy place—very powerful and very healing.”

Janice Knapik drives all the way from Jacksonville, Florida, to enjoy the waters at Salt Springs in the middle of Ocala National Forest. She began visiting springs in Florida as a place to relax and read, but when she developed asthma, she discovered that the water might be healing.

“I did some research and learned that cold water therapy stimulates the immune system,” she said.

Knapik goes to Salt Springs during the week to avoid the crowds on the weekend. “I get there around 9 a.m., and I immediately go into the water.”

“Initially the cold water is a shock, but it is also exhilarating,” she said.

After a morning at the springs, she arrives home invigorated and refreshed—something she does not get from a trip to the nearby beaches near Jacksonville, she said.

Springs in Florida have been sites for healing spas since the 19th century. Wealthy speculators built luxury resorts to accommodate those who arrived to bathe in the bubbling mineral waters.

Many persist, such as Safety Harbor Spa near Clearwater, which offers the amenities of a modern resort complex in addition to the plunge into the healing springs. Originally, according to the resort’s historical information, the spring was identified by Indian shell mound builders almost 2,000 years ago, who believed the mineral springs held mystical and powers.

Sulphur Spring now located in a busy section of Tampa, was once a famous bathing area in Florida. Built in the 1920s by Josiah T. Richardson, the resort attracted people from all over the country who came to the healing waters. This urban spring has had its ups and downs over the decades and is currently fenced off and not available for swimming. Tampa citizens, leaders, and government agencies are combining efforts to restore the spring.

Green Cove Springs in northwest Florida, population 6,800, has the state’s largest non-chlorinated pool fed by the third magnitude spring. “Technically, it’s called a bathing area,” said Mike Null, director of Public Works for the city. The pool is open only during the summer, and the pool’s water is exchanged every few hours from the 3,000 gallons-a-minute spring flow that moves from the pool to spring run and then into nearby St. Johns River.

Springs all over the state are known in their communities for their special features that often include folklore, history, and even mysticism.

For Lane the experience is spiritual as well as physical. “When we go into the springs, physically with our bodies, we can become part of the energy, part of the creativity of life from the Earth herself,” she said.

Art of the Springs

The beauty of Florida’s springs is for most people a fleeting experience. We might picnic, canoe, or plunge into the cold water. We enjoy the experience, and then get back to daily life.

Artists seek to capture the beauty, the emotion and the very “soul” of the springs. Two Florida artists who have become well-known are Margaret Tolbert and John Moran.

Tolbert captures the ephemeral springs on canvas. Her springs paintings hang in galleries, museums and in private collections. She has an installation at Orlando Airport. Some of her works you can hold in one hand and others cover entire walls.

Regardless of the size, there are colors, textures and fractions of light that drift and swirl from her paintings, evoking an emotional response for many who view her works. But you never know, she said, how people interpret art or what they see in one of her expressionistic paintings.

She recalled being told that someone wanted to buy her “blue thing.” Clearly, she said, at that moment her work turned from an impressionistic springs motif to an abstract.

Tolbert has long had a love affair with the springs that surpasses painting. She has taken the time to learn the science of the springs and has published a book that celebrates multidimensional aspects of the springs from hard geological facts to the fantastical adventures of a mystical lady of the springs. “Aquiferious” is a collection of essays, art and photography by Tolbert and others.

Sometimes, Tolbert is subject as well as creator of her works. Those familiar with her work know of the escapades of her alter ego, Sirena, who lives only in the crystal clear springs that remain in Florida.

The illusive Sirena has her own Facebook page where you can see photographs of her dressed in striking attire and floppy hats, under water doing an array of activities: bowling, riding a bike, holding an umbrella, playing tennis. “Sirena,” Tolbert said, “has a busy life.”

She has spent more than 15 years carrying canvas and paints to springs throughout Florida. She sits on rocks at edge or in the springs. She immerses herself in the waters or snorkels to see what is under the surface.

Tolbert sketches underwater on plastic with a pencil. A challenge, she said. “I’m floating along, snorkeling in the current, stuff is moving, and I’m trying to draw a turtle!”

Because she pays attention to the functionality of the springs as well as the aesthetics, Tolbert is keenly aware of their decline. Even if she did not know the facts, she said the changes show up in her paintings.

“I’ll start noticing that I am using interesting different colors. I think to myself, ‘I can make forms out of this green,’ and then I realize that there is more algae in the springs.”

The springs seem darker to her. Madison Blue, she said, was beautiful because of the way light reflected on the bottom.

“Now, though, it is covered with algae. It’s like going into midnight. Still special and jewel-like, just not like it was years ago,” she said.

Photographer John Moran also knows what the springs used to look like. He has photographed hundreds of them. Moran is well known for his landscape and wildlife photography across Florida from the Gulf to Atlantic, in the Everglades, and on the Panhandle.

His works have appeared in numerous books and magazines including National Geographic, Life, Time, Newsweek, and Smithsonian as well as on the cover of the National Audubon Society Field Guide to Florida. In 1982, he was named Photographer of the Year for the Southeastern U.S. by the National Press Photographers Association.

Moran is not pleased with what he sees in the springs. Flows rates are down, and he notes the same dusting of algae and gelatinous mats that Tolbert described.

In February 2010, Moran stood on the steps of the capitol in Tallahassee, Florida, as part of a rally.

He called the springs “gems of the Florida landscape” and gave an emotional outpouring that included facts and solutions as he urged legislatures to protect the springs in Florida.

“How can a state, blessed with the finest springs on the planet, allow this to happen?” he asked.

When the algae began to bloom in earnest, “many of the lovely aquatic grasses died back or became coated with a noxious sludge. And the once crystalline waters turned cloudy and dull,” he said.

Nature photographer John Moran poses on a dead cypress tree left half submerged near Palm Point Park along Newnan's Lake.

Moran has photographed the springs over decades and has an archival record of how they used to be. He is currently returning to many of the places he photographed to document what they have become.

As he catalogs the fate of spring after spring for what he hopes will be another book, the experience is “sad and painful.” He feels compelled, though, to take this journey, he said.

In a slideshow of some of his photographs, Moran wrote, “When the oceans receded, the peninsula we call home emerged and was blessed with an abundance of rivers, lakes and springs.”

“Photography has become the language, in which I best express my gratitude,” Moran said.

Looking for solutions, scientists wrestle with chemistry and mechanics of spring degradation. Environmentalists tell us to stop using so much water and fertilizing our lawns.

Artists ask us to see: to note the slight decline in flow, the shifting hues of the water, changing shapes and amounts of vegetation, and the decreasing fish varieties and populations.

It may be artists who are best able to reveal the importance of the springs and convince us of their worth. For these two artists, at least, the aesthetic splendor of the flowing waters is reason enough to protect their quality.