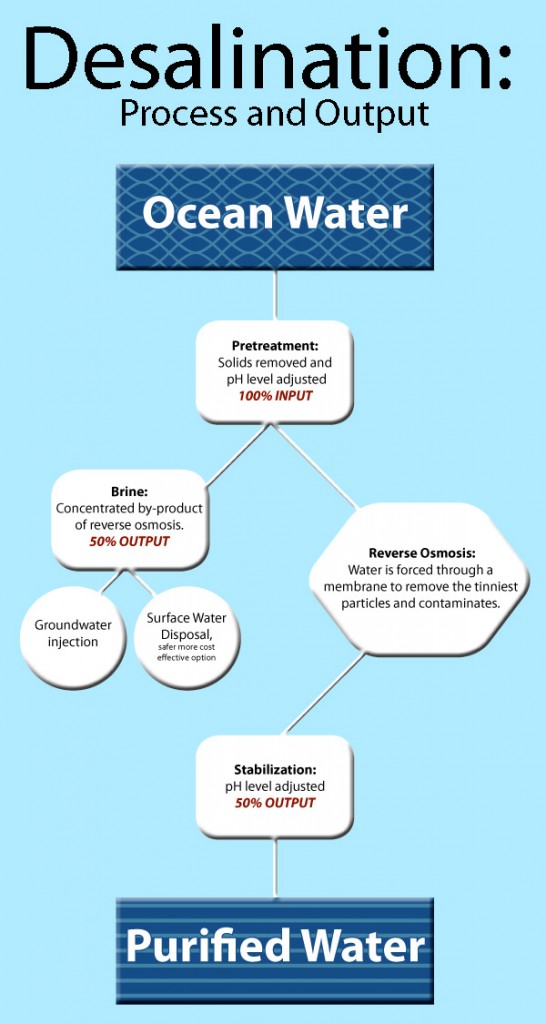

Desalination — in the simplest terms — means turning salt water into potable water. This is one technique scientists and public officials have looked to use to supplement the world’s supply of fresh water.

Daniel Yeh, an assistant professor at the University of South Florida and an expert in green technologies and water issues, explains that even though water is a finite resource, we can develop different ways to supplement or regenerate it for human consumption.

With less than one percent of the natural water supply accessible for drinking, the use of desalination has grown worldwide in response to an emerging global potable water crisis. The World Health Organization estimates that nearly 20 percent of the world’s population lives in countries where water is scarce.

Desalination Plants Around the World

Most of the world’s desalination plants operate in the Middle East where the amount of naturally occurring fresh water could never support the population. The United States has one of the largest supplies of viable fresh water, but desalination is still an attractive method for some locations. The Tampa Bay Seawater Desalination Plant is the largest plant in North America. It produces 25 million gallons per day (mgd) of clean drinking water to Hillsborough, Pasco and Pinellas counties, as well as the cities of St. Petersburg, Fla. and Tampa.

The average output for safe, drinkable water from the amount of sea water put into the desalination process is roughly 50 percent, according to Paul Chadik, an associate professor in potable water systems engineering at the University of Florida. The Tampa facility, however, has an average fresh water recovery of about 57 percent.

Among the problems with desalination are the amount of energy it uses and the possible adverse environmental effects. Desalination’s critics are concerned about the process’s potential for harming the ocean and ocean life and the possibility that people will continue to over-consume rather than conserve water.

Dr. Chadik believes that, like all new forms of technology, desalination still has much room for improvement in the amount of energy it uses, the cost and most importantly its environmental impact.

“I think [desalination technology], just as it has improved over the past 50 years since its first conception, will continue to improve,” Chadik says.

Chadik says there are processes that eliminate waste byproducts entirely. But these processes, having just been introduced in the last decade, are still not cost effective enough to be applied on a municipal level. But the possibility of doing so could be very real in the next ten years.

He and many others are hopeful for the future of desalination technologies and hope for continued support while as the technology develops and improves.