Visitors to Ginnie Springs looking out at the Santa Fe River. There is visible algae in the background, though the spring's waters were clear.

On a Tuesday afternoon, Ginnie Springs near the city of High Springs, Fla., is filled with divers, swimmers and people relaxing in the water. For a weekday, there are more people than you’d expect.

Every year, millions of people visit Florida’s springs and rivers, bringing their money with them. An annual report compiled by the Florida Park Service estimates that the 15 most popular of Florida’s state parks bring in combined revenue of over $12 million. In addition, visitors to places such as Ginnie Springs, a private spring, and Ichetucknee State Park have a sizable economic impact on the nearby towns.

In many parts of Florida, natural beauty is an economic asset. At least one person thinks that might change.

Trouble in paradise

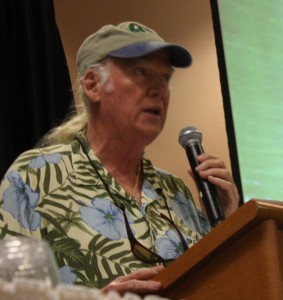

Roland Loog, director of Visit Gainesville, said that the waters of the Santa Fe and Ichetucknee rivers, as well as all the connecting springs, have deteriorated over the last 12 years.

“The water was crystal clear,” said Loog, when describing his childhood experiences with the Ichetucknee River. “Today, the water definitely has a greenish hue.”

He said that the Suwannee, the Santa Fe, and all the connected bodies of water have suffered. Algae blooms, decreased water levels, and weaker water pressure are among the problems he listed.

Loog said the town of High Springs has “economic woes” directly related to declining conditions in the springs and the Santa Fe River.

Marc Bryan, of the Cave Country Dive Shop in High Springs, disagrees with Loog.

“Where else are people going to go? We still have the most beautiful springs,” said Bryan. “It’s not like they’re going to say the High Springs area is terrible and go to Tampa.”

Bryan said High Springs is suffering due to the poor economy nation-wide, not because of worsening conditions in the nearby springs and river.

He doesn’t deny that he is concerned about algae, but he is reluctant to believe there is a long-term problem with decreasing water levels.

“It’s a timing thing,” he said. “We could have this conversation three weeks from now and things could be different.”

During the the six months the dive shop has been open, one employee estimated about 500 customers have come through.

“Have you ever, ever heard one person say that business is bad because of algae or the water level is down?” Bryan asked Marissa Lasso, another employee at the dive shop. “No,” she replied.

Gently down the stream

Jim Woods, CEO of the Santa Fe Canoe Outpost in High Springs, said that problems with the springs and the river are something he is “extremely concerned” about. Although his business hasn’t seen a decrease in customers, he worries that lower water levels will make canoeing too difficult for his patrons.

Woods said the canoe outpost has had about 5,000 to 7,000 customers over his last business year. An average year, he said, customers number 3,000 to 5,000.

Even though people are still renting his canoes, Woods said that the state of the water has made his cost of business go up.

“We’ve had to adjust,” he said.

Woods’ bookkeeper, Ross Ambrose, said that the water levels have forced the canoe outpost to change where it can put its clients in the water.

“We used to put people in the water right here,” he said. “Now we have to drive them to the next bridge. There’s a cost to our clients.”

In addition, Ambrose mentioned other issues, such as problems navigating canoes in low water and algae making it difficult for divers to see underwater.

Ambrose said he doesn’t think lower water levels, increased algae and more pollutants in the water are temporary problems. Lax regulations and more water use in Jacksonville are to blame, he said.

Ambrose said it is entirely possible that High Springs could eventually end up like White Springs, in Hamilton County, Fla., where phosphate mining disrupted the water flow of the nearby springs. The nearby waters ultimately vanished, causing economic devastation for the town which once featured eloquent destination hotels.

Ecotourism’s secondary business

Aside from canoe rental shops and similar places, other businesses in High Springs rely on tourist cash.

Lucie Regensdorf, owner of the Grady House, a bed and breakfast in High Springs, estimates that 90 percent of her customers are people coming to see the river and springs.

“Ecotourism is huge here,” she said. “Most people come here for the river.”

Her business had about 1,600 customers in 2011. Her best year was 2008, when she had 1,800 customers, she said.

Regensdorf beleives that if the springs and rivers were not in good condition, people would stop coming to High Springs.

“It would hurt my business and a lot of other businesses in town,” she said. “People who think that rivers are important are going to try and protect them, and hopefully they can prevail and get the city commissions and county commissions to do the right things.”

Dan Mijajlovic, owner of the Springs Diner in High Springs, said that during the summer, he gets around 6,000 customers a month. He estimated that nearly half of those patrons are tourists.

Differing viewpoints

Opinions by local business owners on the state of the Santa Fe River and local springs have varied. Loog and Ambrose expressed a pessimistic view, while people like Regensdorf and Bryan said things are good.

A senior employee with Ginnie Springs, who did not wish to be identified, said there is no problem with the water conditions in the area. Ben Harris, former park manager for the Suwannee River Wilderness Trail, agrees.

“The water is better than it’s ever been,” he said. Harris said he believes that the springs and rivers all throughout North Florida have been improving.

“The state has made a concerted effort to make sure there is no pollution,” he said.

Harris said lower water levels are caused by a recent drought and fluctuate with the weather.

The big picture

High Springs is just one place that has capitalized on water tourism. There are many other similar towns that benefit from Florida’s scenic rivers and springs.

In its 2011 annual report on the economic impact of springs in the state, the Florida Park Service looked at the direct economic impact of Florida’s springs from 2009 to 2010. It gathered this information by studying how much money tourists spent in nearby areas while visiting the springs.

Blue Springs, near DeLand, Fla., brought nearly $20 million into surrounding areas.

Ichetucknee Springs, northwest of Fort White, Fla., attracted over $7 million dollars into its local economy.

According to the report, the top 15 most popular springs in Florida had a combined economic impact of $114 million that fiscal year.

Happy campers

Jeff Reeves, a diver originally from Michigan, has no complaints about the water at Ginnie Springs. He has been cave diving in Florida since 1991 but only moved to the state five years ago.

‘The diving brought me here,” he said.

He suits up near a spring known as The Devil’s Eye. Reeves said the water looked just as good as it always has.

“This is one of my favorite spots.”

People basking in the sun at the mouth of the Santa Fe River, where it branches from the Suwanee. They were sunbathing and swimming in clear water.

A sandbar on the Suwanee River, a popular place for lazy afternoons. These people were enjoying the sunny day.

Visitors to Ginnie Springs looking out at the Santa Fe River. There is visible algae in the background, though the spring's waters were clear.

Visitors floating around Ginnie Springs. There were a surprising number of people present, considering it was a Tuesday afternoon.

Divers at Ginnie Springs resurfacing after examining the bottom of the spring. Many of the divers present that day were from out-of-state.

A massive algal bloom at the Santa Fe River, taken near the River Rise Preserve State Park. There was very little activity here, especially compared to the more scenic parts of the river.