By Jennifer Adler

Green: the color of springtime leaves, the flowing saw grass of the Everglades. It’s synonymous with nature, outdoors, and perhaps recycling – and also the most recent addition to Margaret Ross Tolbert’s palette.

As algae took hold, Margaret Tolbert started using more greens in her paintings. Beneath the surface, algae now dominates many springs.

Fanning Spring was Tolbert’s favorite place to paint. She would immerse herself in its crystal waters and spend hours by the Suwannee River spring, painting life-sized canvases of vibrant color depicting the surreal spring at her feet and the feeling of being underwater. For many years, she studied at Fanning, launching an exhibit at Northwest Florida College in 1997, made up of 11-foot-tall paintings boasting bright blues and liquid light.

But over time, she began using more greens.

“I was so pleased I developed a new formal vocabulary using colors… like green,” Tolbert remembered. French painter Toulouse Lautrec used a lot of greens in his studies, so she thought it was interesting that she was doing the same. But in Tolbert’s case, the color change signified something greater: degrading springs.

“It turned out I was just painting what I saw – new and luridly green colors of burgeoning algae.” Her palette had shifted as the algae took hold.

Margaret Tolbert’s 1997 exhibit “Portals and Passages” at The Arts Center, Northwest Florida College, Niceville, Florida. Photo by Jack Gardner.

~~~

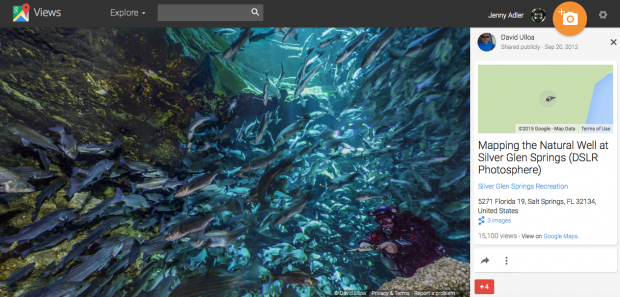

To the trained and untrained eye alike, many of Florida’s 1,000-plus springs still sparkle. From swirling ‘fire water’ overhead to brilliant blues and gin-clear underwater caves, they are remarkable to see and explore. But over the past 15 to 20 years, overwhelming amounts of algae have come to dominate many of the once-clear springs.

Despite their decline, many springs are still remarkable. At Ginnie Springs, divers marvel at the swirling ‘fire water’ above Devil’s Ear. Tannic water from the Santa Fe swirls with clear spring water to create this otherworldly effect.

One of the two main types of algae, Vaucheria, is a green algae, while the other, Lyngbya, is a cyanophyte that forms dense, brown mats. Scientists began to study the shift in vegetation when the Florida Springs Task Force was created in 1999, and managers have since scrambled to make positive changes. But it’s a tricky problem to explain, especially to the majority of Floridians who have never seen a spring, and it has proven an even more difficult problem to solve.

As scientists analyze water samples and study groundwater flow, another group of keen observers has also recorded the changes in spring ecosystems. Theirs is a beautiful yet heartbreaking mélange of artistic output, serving as a visual history of the springs and their decline. It may also turn out to be one of the best routes to saving them.

Art, politics, and the river of grass

“This idea that swamps and wetlands are these dangerous, spooky places only worth draining isn’t a new idea – this is something that’s pervaded centuries of our being here,” says Mac Stone, a conservation photographer who recently published a book about the Everglades.

Long seen as a wasteland of uninhabitable swamp, the Everglades is now a World Heritage Site, a wetland of international importance. Photographer Clyde Butcher helped instigate this dramatic shift in ideology; he ventured into the storied swamp and returned with photographs that changed people’s perceptions of the Everglades.

Photographer Clyde Butcher brings the Everglades and other wild Florida landscapes to people through large-format black and white photos. Butcher hopes these photos will inspire people to go visit these places themselves and perhaps fall in love with these amazing ecosystems. This photo, “Ochopee,” is one of Butcher’s popular photographs of the Everglades. Photo courtesy of Clyde Butcher.

“One of the problems that we have is that people do not leave the city, they do not feel safe in nature,” says Butcher. “Using photography, we can get them introduced to these natural wonders and maybe they’ll go visit.”

Through large-format black and white prints, he has brought the Everglades to “people who would never have dreamed of setting a polished Italian loafer in the swamp…,” write Tom Shroder and John Barry in the Butcher biography Seeing the Light. Because of Butcher’s photos, these loafer-wearing Floridians began to care, and as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “declared a war on swamps,” Butcher brought the picturesque wetland to people’s living room walls.

The power of pictures

Like the swamp under siege, changes in the struggling springs have become political. Bipartisan environmental issues and newspaper headlines depicting war are common: environmentalists versus government, state government versus federal government. Battles over water quality criteria and numeric nutrient standards have plagued courthouses and Florida Department of Environmental Protection meetings like algae plague the springs.

“Water is inextricable from politics in Florida – no matter how true your message is with words, they’re laden with bias,” says nature photographer John Moran. “Photos have no baggage. There’s something undeniable about the power of these pictures,” he added.

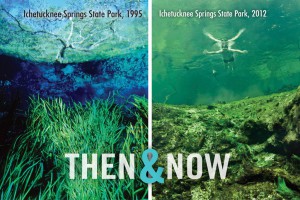

This is one of the reasons Moran and artist Lesley Gamble started the Springs Eternal Project. The exhibit portion of the project highlights Moran’s ‘then and now’ springs photos, which have grabbed the eyes and won the hearts of viewers statewide. Moran’s archives date back to 1973, the year he started college at the University of Florida – also the year he bought his first nice camera, a Nikkormat with a 50mm lens. Pairing photos from the 70s – 90s with those from more recent adventures (post 2000), Moran now brings the before-and-after reality of the springs to museums, living room walls, and university buildings. He even puts them in the hands of politicians.

John Moran’s powerful “Then & Now” photographs have been incredibly influential in both public opinion and political endeavors. The Springs Eternal exhibit features several “Then & Now” comparisons, this one in particular demonstrating the loss of native submerged aquatic vegetation at Devil’s Eye spring on the Ichetucknee River. Photo courtesy of John Moran / Springs Eternal Project.

“It’s pretty apparent that the Springs Eternal project, along with a whole host of other players, made a meaningful difference not necessarily in terms of outcomes but changing what the candidates are talking about,” says Moran.

He is currently traveling throughout Florida spreading his springs gospel and sharing his photos from the past 40 years that document the decline of the springs in a way that immediately grabs peoples’ attention.

Moran’s Springs Eternal cofounder, Gamble, has a PhD in art history and teaches a University of Florida course called ‘Water, Art, and Ecology.’ She spearheaded the other two projects that round out Springs Eternal, including the Urban Aquifer and the project’s website.

Her blue-green eyes flicker with excitement as she shares her insights about the power of art: “Art can reach people at levels that are not rational, obvious or conscious,” she explains. “Art can offer viewers agency; they figure out for themselves how they want to respond (or not) to the artwork, to the sensations, emotions, or ideas that emerge in that interaction.”

This is exactly what Tolbert hopes to achieve with her paintings.

Artist Margaret Tolbert’s immersive paintings elicit curiosity and wonder. This is “Entering the Springs,” one of Tolbert’s life-sized canvases that engages viewers and invites them to jump in. [Oil and mixed media on canvas, 90 x 90 inches, 2006.] Photo by Randy Batista.

This empowerment of viewers – a personal journey through the painting that elicits curiosity and acceptance – may prove powerful for helping people understand issues surrounding springs, including the direct connection between the springs and their backyard irrigation or fertilizer use.

Shifting baselines

The same problem that Clyde Butcher confronted in the Everglades affects the springs today: some photos are “too pretty” to show the degradation. Free of a picturesque vision of springs in their apparent former glory, it’s a challenge to communicate the idea that the springs have changed because many are still gorgeous, despite the algae.

The scientific term for this is “shifting baselines,” first coined in 1995 by fisheries biologist Daniel Pauly in a scientific paper published in the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Basically, chronic, slow changes occurring in an ecosystem over time can be difficult to notice. Because these changes go unnoticed at first, the original condition (or “baseline”) is shifted and it’s hard to evaluate how much an ecosystem has suffered. If people have never seen a spring, it makes this concept even more difficult. In many springs, there is currently very little natural vegetation remaining. But to a first-time visitor, this is their “normal.”

Moran recounts the story of a couple that escaped the south Florida sprawl to get married at the secluded Ichetucknee River, the place Archie Carr famously named “the most beautiful landscape in the world” in his book A Naturalist in Florida. Moran took photos of the couple in the headspring, noting that they were very much in love and engulfed by the beauty of the spring, having never seen one before. He struggled with the idea of confronting these blissful lovebirds to tell them that they missed the spring when it actually looked pretty. He couldn’t bear to tell them that the spring’s algae-laden waters were nothing compared to how they looked before 2000. So he did something else.

“I didn’t want to be the one to burst their bubble,” he says. “But I juxtaposed the pictures of them with an identical photo from 20 years ago and it makes for a pretty compelling comparison shot.” Using these ‘before and after’ comparisons, he can let audiences see for themselves how the springs have changed.

Tolbert feels similarly conflicted when people think a degraded spring is magnificent. “I don’t really say that much… I might show them the old pictures,” she says. “It’s hard to stand there and say ‘well, it used to look better’…” It’s challenging to get across the idea that many springs are only greenish shades of their former selves.

Nature photographer Mac Stone, who has seen the splendor and suffering of the Everglades firsthand, says it’s a fine line: “You’ve got to show the beauty of it but you’ve also got to show the maybe not so pleasing side. If you’re constantly shooting to put photos up on people’s walls, then you’re not telling a story… it’s not all sunshine and rainbows,” he explained. “But you’ve got to have a balance of both or you won’t get people on board to listen to you.”

And despite the sad state of some springs and parts of the Everglades, Stone says there are still a lot of pretty photos to be taken: “… you have to give them reason to celebrate too, and there is plenty of reason to celebrate.”

Gamble agrees: “We need to enjoy what we do have, honor and celebrate the springs as unique and truly ‘wondrous.’” But there’s a caveat: “The additional pressure with springs issues is that we’re short on time,” she added. So where do we go from here?

Splashing forward

When Carleton Watkins piled his bulky cameras and giant glass slides on mules and trekked 75 miles into Yosemite in 1861, he returned with photos that changed the future of the remote valley. His photographs offered many Easterners their first glimpse of Yosemite, which then became an icon, an extraordinary place people wanted to visit and preserve. When the photos made their way into President Abraham Lincoln’s hands, they influenced his decision to sign the Yosemite Valley Grant Act in 1864; the creation of the National Parks system followed shortly thereafter.

After Watkins, the celebrated work of Ansel Adams also influenced legislation, along with the public’s relationship with nature and wilderness. During his 37 years on the Sierra Club board (1934-71), Adams and his photos made their way to Washington D.C. and piqued the interest of policymakers, playing a key role in several decisions, including the designation of Kings Canyon National Park in 1941.

Bruce Mozert’s pioneering underwater photographs garnered national attention for the springs, beginning in the 1940s. Photo courtesy of University Press of Florida.

Many miles southeast in Florida, Bruce Mozert was busy crafting some of the first underwater cameras. He arrived at Silver Springs in 1948 and produced black and white images of air-clear Silver Springs. His famous photos of people doing everyday activities underwater – from mowing the lawn to drinking champagne or having a barbeque – generated national publicity for the springs, attracting tourists and celebrities to their clear waters.

More recently, Carlton Ward pioneered a 1000-mile journey through wild Florida: The Florida Wildlife Corridor Expedition. The resulting photos and documentary remind Floridians that wild Florida still exists; despite rampant development, it is still possible to venture from the Everglades up to the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and never set foot in a subdivision or patch of St. Augustine grass. Additionally, his cattle ranching photography has brought people together from opposing ends of the political spectrum for land preservation in central Florida.

With their paintbrushes and lenses, their passion and creativity, artists of all types have played integral roles in saving those places that inspire their work. From Yellowstone to the Everglades, the history of artists showing audiences why natural icons are worth saving offers hope for the future of the springs – especially given the numbers of talented artists at work to show them to Floridians.

“It’s going to take a bunch of different mediums,” says Stone. “It’s going to take poets, it’s going to take writers, it’s going to take photographers, filmmakers. It’s going to take a whole society to make the sea change,” he says. “And we are. We are doing it, slowly.”