By Cynthia Barnett

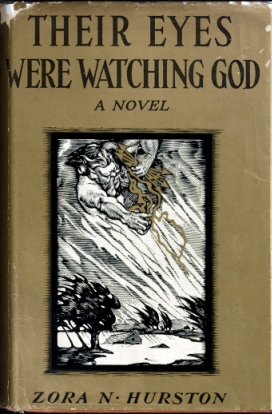

The National Hurricane Center’s 5-Day forecast for Tropical Storm Erika draws a bead on Lake Okeechobee, the 730-square mile icon of so much of what’s gone wrong with water in Florida. A 1928 hurricane that hit there sent the lake bursting through and over its earthen dike, killing 2,500 people, most of them poor black laborers who drowned in the agricultural fields south of the lake. Zora Neale Hurston captured the calamity in her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. In the wake of the storm, the Army Corps of Engineers began to build a massive levee around Lake O.’s south rim. After the 1947 wet season dumped 108 inches of rain in South Florida, Congress authorized the Central and Southern Florida project to try and tame the capricious climate once and for all. The engineers ultimately built 1,000 miles of canals, 720 miles of levees, sixteen pump stations, two hundred gates and countless other tack. The harm to Florida’s great Everglades, its water and wildlife became clear before the project was even finished.

In next week’s Environmental Journalism class — the Monday Erika could make a Florida landfall — students will hear from Florida Sea Grant Executive Director Karl Havens on Everglades restoration and its viability amid climate warming and politics boiling. But what about the immediate safety of those who live south of the lake? Student readings for Monday include the Miami Herald’s Curtis Morgan’s award-winning story “On the brink of disaster” that shows the levee ringing Lake O. today is another disaster waiting to happen.

Fortunately, the current lake level is lower than in the past few years — about twelve feet, six inches, says the Army Corps’ John Campbell. The lower the level the safer; the higher, the greater the pressure and chance of a breach. There’s about a 5 percent chance of a breach at 16-foot water levels and 45 percent chance at 18 feet. Failure is expected at 20 feet. In 2012, Hurricane Isaac dumped enough rain as it traveled over Florida to raise Lake O. from about where it is today to sixteen feet, Campbell says.

The Corps tries to keep the lake between 12.5 and 15.5 feet in a delicate and controversial balance of water releases that can foul estuaries and fuel harmful algae blooms along Florida’s southeast and southwest coasts. Since 2007, the agency has spent $500 million on its project to bolster the dike, including new concrete barriers that offer “some improvement in the risk picture,” says Campbell. Yet the project, separate from Everglades restoration, will not be finished until 2020.

No hurricane has made direct landfall in Florida for 10 years. If Erika breaks the hurricane drought, the days leading up to landfall are a top-of-the-news opportunity to talk about the region’s long-term adaptation to rising seas and rougher storms. Who will take advantage? Will meteorologists talk about resilience beyond the weekend trip to Home Depot? Which reporters will take the time to point out that successful Everglades restoration — restoring the natural pathways for water to move through South Florida — could help protect us from future storms by absorbing floodwaters and keeping saltwaters at bay? As Zora Neale Hurston wrote in Their Eyes Were Watching God (she was writing about women): “The dream is the truth. Then they act and do things accordingly.”