A request by Adena Springs Ranch, near Fort McCoy, Fla., to withdraw 13.2 million gallons a day from the Floridan Aquifer is being challenged by hundreds of people in north central Florida.

Owners of the 30,000-acre cattle ranch have applied to the St. Johns River Water Management District to pump more water daily than the 12 million gallons that the city of Ocala withdraws for public use.

The application is currently in the hands of the water management district for review.

Supporters of the project say that it will create local jobs and provide a clean industry for Marion County. Adena Springs Ranch wants the volume of water to irrigate land to raise grass-fed cattle.

Audience at the April 3 public forum at the Ewers Century Center Klein Conference Room at College of Central Florida on water consumption and the Adena Springs Ranch permit.

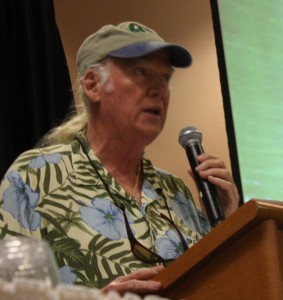

Roy L. ?Robin? Lewis, panelist at the public forum about water consumption and the Adena Springs Ranch.

Karen Ahlers, environmental activist; Debby Johnson, paralegal with Southern Legal Counsel; and Buddy McKay, former lieutenant governor and board member Southern Legal Counsel.

Adena Springs Ranch officials were invited to participate in the two-hour presentations and panel discussions, but declined according to moderator and president of the Silver Springs Alliance, Andy Kesselring. Present at the evening meeting were some members of the Marion County commission, as well as former Florida lieutenant governor Buddy McKay, a board member of the Southern Legal Counsel and a supporter of environmental issues in Florida. ?I am passionate about preserving Florida?s water,? said McKay, best remembered for his work to prevent stop the Cross Florida Barge with Marjorie Harris Carr. Lewis handed over a personal check for $5,000 to Neil Chonin of the Southern Legal Counsel to begin the support for legal action. Ahlers said about $250,000 are needed to monitor the approval process, gather scientific evidence of the negative impacts to water quality and quantity and to prepare a legal case should the permit be approved. ?The threat of a lawsuit and close scrutiny of the application process may be the only way to protect the interests of the public,? Ahlers said. ?We?re in this for the long haul. We will go forward until we have exhausted every legal remedy.? The challenge is not just drinking water, she said, but entire ecosystems. ?This is not just a Marion County issue. It is a statewide issue. A test of whether or not citizens of Florida are going to throw up their hands and allow corporate and political interests to destroy what is left of Florida?s natural resources,? Ahlers said.

Second group of panelists for the public forum about water consumption and the Adena Springs Ranch. From left to right: Mike Registers, St. Johns River Water Management District; Barbara Fitos, executive director Community Foundation for Ocala Marion County; Neil Chonin, environmental lawyer with Southern Justice Association; Roy L. ?Robin? Lewis, professional wetland scientist; Bob Knight, director of the Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute; Guy Marwick, executive director of the Felburn Foundation, and Andy Kesselring, president of the Silver Springs Alliance.